The number one piece of advice I give to new VCs launching their investing careers

I talk to lots of VCs who are joining venture firms or moving into checkwriting roles at their current firms. Over time I've realized that I give them the same general advice and wanted to share it.

In the past few years, I’ve had the chance to speak with quite a few people who are moving into their first full-time investor roles, either as brand new VCs or people who are getting promoted into investing roles with discretionary checkwriting responsibilities. The most common question I get from these folks is what advice I have for them as they make this transition. It’s hard to give generic advice - every firm is different and every person comes to the job with a different set of prior experiences and expectations about what the job will entail. For starters, I tell everyone the same thing:

I have seen far more people damage their future career prospects in venture by trying to do too much too soon as opposed to being patient and going slower when they first get into the business

Unlike operating jobs, the feedback cycle on most venture investments is really long and winding; it often takes a very long time for the best investments to mature, and it takes many people some time to see enough companies to know what good looks like. Resisting the urge to simply do something (the classic difference between activity and productivity) is hard to overcome, but most people are well served by taking things slowly at first.

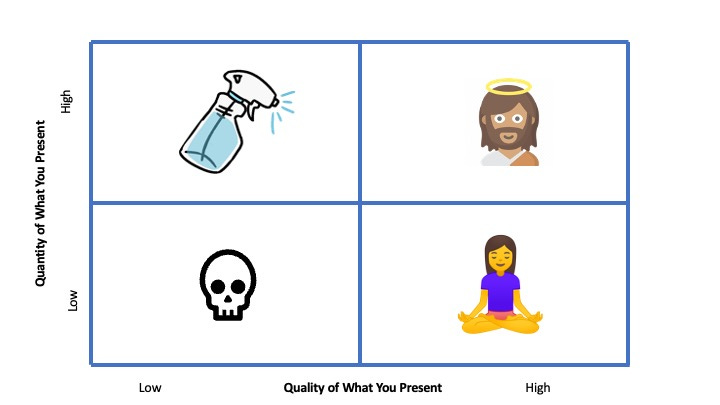

In the last month I’ve spent more time talking to people who are looking to level up in their existing venture roles; they are already working in venture, but are moving into a role where they have the ability to bring companies to the partnership for consideration and the ability to write checks for companies that they think are interesting. Upon reflection, I think I have a simple matrix that I’ve been using to talk to people about how to approach this challenge:

Most venture funds evaluate new checkwriting investors along three dimensions. Different firms might describe these attributes differently, but here’s what I have observed in talking to people across firms:

Access - Do you have access to companies that are good investments?

Judgment - Do you have the ability to determine the set of companies where you should focus your time and attention? The better the pool of companies you see, the harder it is to tell the difference between merely good and great companies.

Discretion - Do you have a sense for which companies to elevate for discussion and consideration; this is a combination of access and judgment, and I think it’s an essential skill when working in a partnership.

Many partnerships use their team meetings to discuss companies that some portion of the group finds interesting. The standard for what qualifies as meeting-worthy varies across firms, but I do think many firms use group meetings to focus the firm’s energy on the most interesting opportunities. As a new investor, there is a tension between bringing things to the partnership to show that you are finding good things and working hard and being judicious about what you elevate for discussion. Silly emojis aside, let me describe what I am trying to capture with the four quadrants above:

High Quality and High Quantity (God) - This is obviously nirvana. I have met very few VCs who consistently bring lots of high quality opportunities to their partnership. Most VCs will do a few investments per year per partner, so this is a very hard quadrant to occupy but is obviously desirable if you can do it.

High Quality and Low Quantity (Zen Yogi) - This is the person in your partnership who doesn’t bring things for consideration often, but the things they do present are of high quality and always worthy of the group’s attention. You don’t worry about how this person is spending his or her time, as they are finding great companies on a regular (but less frequent) basis.

Low Quality and High Quantity (Spray Bottle) - This is not a great place to end up. The spray bottle is the person who brings a lot of lower quality opportunities to the partnership and chews up time talking about companies that aren’t realistic investment opportunities. The risk for this individual is that they create a negative feedback loop where the things they bring to the partnership are perceived negatively due to the sheer volume of low quality things they bring to the group. It’s easy to question both this investor’s access and judgement based on what they are elevating for discussion and consideration. This is the most common failure pattern I see for new investors.

Low Quality and Low Quantity (Dead Zone) - This is honestly the worst place to end up. This is the person who doesn’t elevate much to the partnership for discussion. Even worse, the relatively few companies that are presented are not seriously considered. This is the ultimate doom loop as it calls into question the person’s access, judgment, and possibly even their level of effort in seeking out great opportunities.

Joining a venture firm or moving into an investing role can be an incredibly stressful transition for many people. I hope this articles provides some framework and guidance to those who are considering the transition or find themselves in the middle of it and looking for a way to think about how to best navigate it.

Thank you for your valuable insights, Charles! As a newcomer to the VC landscape, my initial inclination has been to pursue the Spray Bottle strategy while I navigate the intricacies of successful deals. This helped me realize that adopting a more mindful and strategic Zen Yogi approach is crucial for long-term success.

Love this post and TOTALLY agree!